THE SHOULDER COMPLEX

Similar in structure to the hip the shoulder is a ball and synovial socket joint. It is a more complex joint because of the range of motion that is required for day to day movements. Not only do we use our shoulders for practical purposes like lifting and carrying but we also use our shoulders to express ourselves. We communicate with our shoulders in body language and gestures. They curl forward when we are feeling vulnerable, tired or cold and they open back when we are happy, proud and enjoying the sun. Similar to a dog's wagging tail you can tell a lot about a person by their shoulder language. We carry our emotions in our shoulders and often this is where we see and feel the effects of stress in our bodies. It is also one of the most used body parts in idioms - we carry the weight of the world on our shoulders; stand shoulder to shoulder; give someone the cold shoulder; and offer a shoulder to cry on.

To make this complex joint easier to understand I will break it down into – the structure of the shoulder; the shoulder blade movements; and the shoulder joint movements with their assisting muscles. Having a basic knowledge of this joint will help keep the integrity of this important joint during your practice. When you get a clearer picture of how all the components work together you will get a deeper understanding of the joint in action as you practice the accompanying shoulder sequence below.

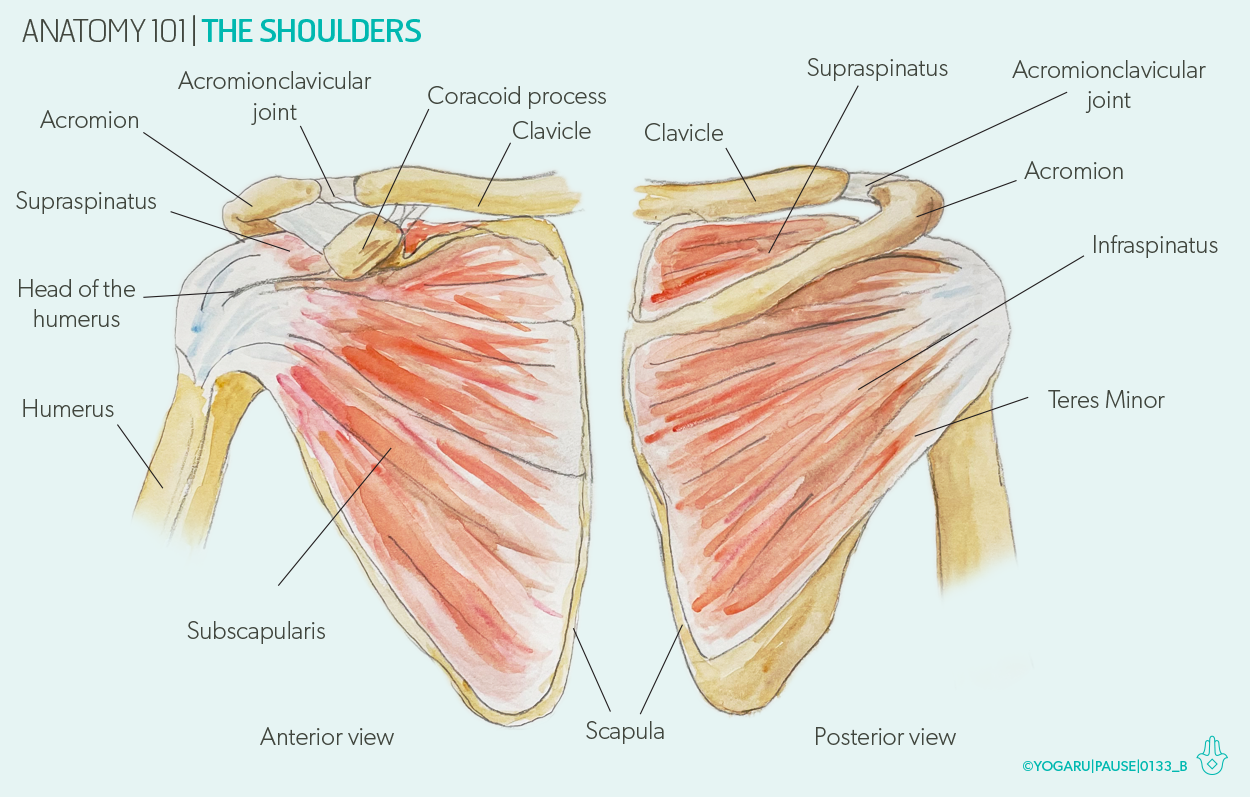

THE STRUCTURE OF THE SHOULDER

The shoulder is the most mobile joint of the body. The structure of the joint, which gives it this mobility, is the main reason it is considerably less stable than the hip joint and more prone to injury and dislocation.

The shoulder is made up of three bones – the shoulder blade (scapula), the arm bone (humerus) and the collarbone (clavicle). There are three joints that work together as a unit to form the shoulder complex:

The glenohumeral (GH) joint – which is a ball and socket joint made up of the head of the humerus and a shallow cup at the side of the scapula called the glenoid fossa.

The acromioclavicular (AC) joint – which connects the clavicle with the scapula and assists the scapula in shoulder abduction and flexion.

The sternoclavicular (SC) joint – which connects the medial end of the clavicle with the sternum and helps us lift our arm above shoulder height.

THE MOVEMENTS OF THE SHOULDER JOINT

Below there is an illustration of the six movements of the shoulder joint:

Flexion – where the arm lift forward and up, the scapula elevates and upwardly rotates.

Extension – where the arm reaches back and up, the scapula depresses and downwardly rotates.

Adduction – where the arm moves towards the midline, the scapula downwardly rotates.

Abduction – where the arm moves away from the midline, the scapula upwardly rotates.

Internal rotation – where the arm rotates inwards, the scapula protracts.

External rotation – where the arm rotates outwards, the scapula retracts.

THE MOVEMENTS OF THE SCAPULA

Below there is an illustration of the six movements of the scapula:

Elevation – where the scapula lift up

Depression – where the scapula lower down.

Retraction – where the scapula move towards each other.

Protraction – where the scapula move away from each other.

Upward rotation – where the outer corners of the scapula rotate upwards.

Downward rotation – where the outer corners of the scapula rotate downwards.

THE MUSCLES OF THE SHOULDERS

For those of you who love to go deeper into the actions of the shoulder joint I have also listed the six movements of the shoulder joint and scapula with their assisting muscles in the chart below. Grouping the muscles to the action rather than looking at each muscle in isolation gives a more experiential understanding.

THE ROTATOR CUFF

The anatomy of the shoulder is not complete without a mention of the rotator cuff. The rotator cuff consists of four muscles which form a ‘cuff’ around the head of the arm bone (humerus) and the shoulder socket (glenoid fossa). Their main job is to work collectively to stabilise the head of the arm bone (humerus) in the shoulder socket (glenoid fossa) and help prevent the joint from dislocating. Each of the four muscles also assist in the following movements:

Supraspinatus – shoulder joint abduction.

Infraspinatus – shoulder joint external rotation.

Teres minor – shoulder joint external rotation.

Subscapularis – shoulder joint internal rotation.

EXPLORING THE SHOULDERS IN YOUR PRACTICE

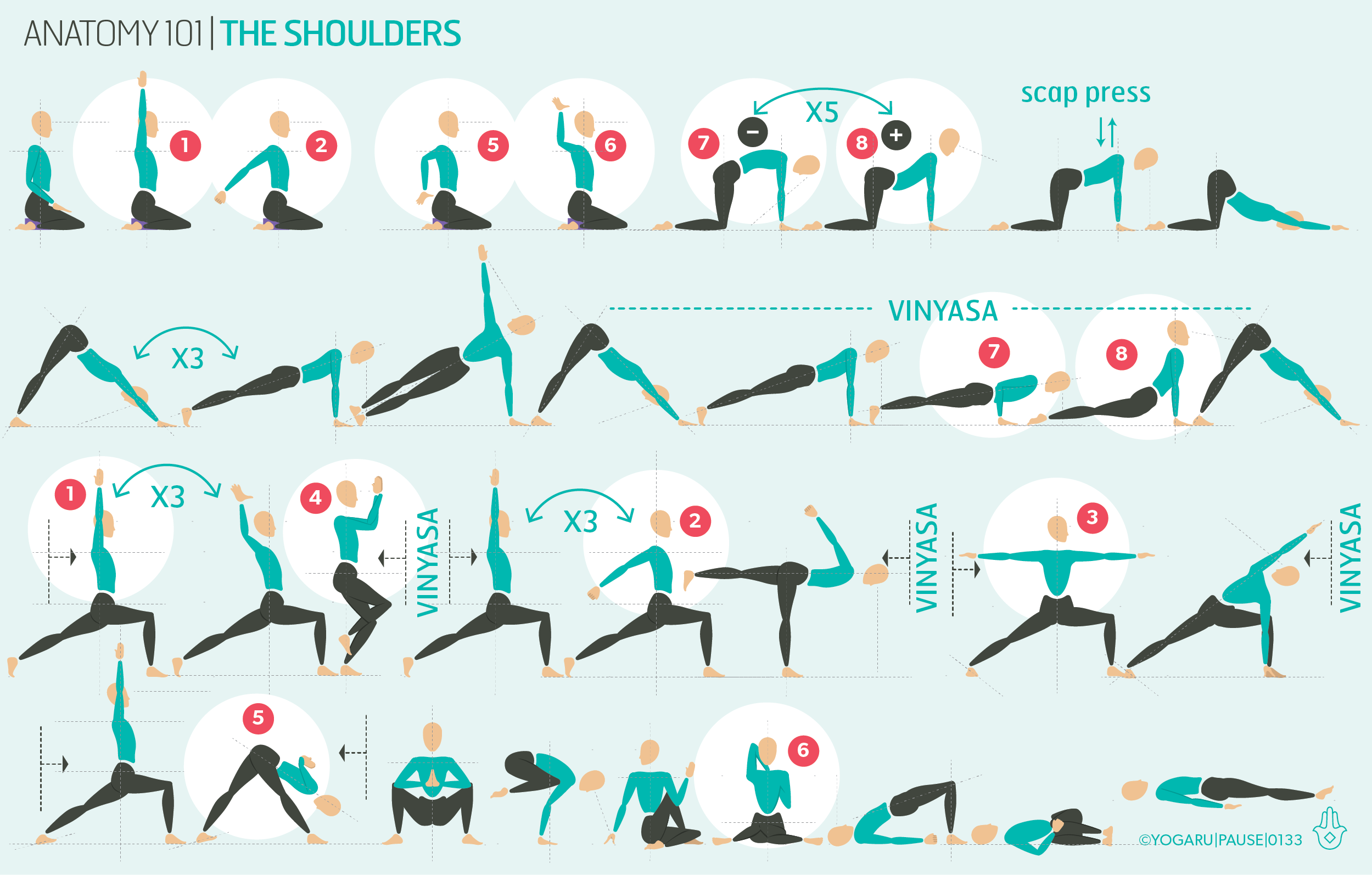

We use our shoulders a lot during our yoga practice. We lift and extend them, we press into them to hold our weight and we wrap them around our bodies. In this sequence bring your full attention to the sensations of stretching and strengthening in your shoulder joint. Remember that muscles work in tandem to each other so when you feel a stretch on one side the other side is most likely strengthening. Look for each side to build a three dimensional picture of the shoulders in each pose, especially the poses I have highlighted as the six movements of the shoulder. The sequence is designed to build a well rounded shoulder focused practice and each pose has a role to play. For the purpose of simplicity, and understanding the movement of the shoulder and scapula, I have highlighted the six movements twice – once as you warm up and once in the flow of the sequence.

ALIGNMENT CUES

This sequence will bring you through the six movements of the shoulder – flexion, extension, abduction, adduction, internal and external rotation. Concentrate this practice on your shoulders and move mindfully with curiosity as you move through the poses. The sequence is numbered to highlight sample poses from each movement of the shoulder to give you a better understanding of the role of the shoulder joint in the pose. The seated poses bring you into shoulder flexion, extension, external rotation and internal rotation. Cat & cow will bring the scapula into protraction and retraction which helps the scapula move freely in preparation for other shoulder work. Below are the asana which are highlighted in the sequence and the correlating arm and scapular movement:

1 – Flexion - Seated arm warm up & Ashta Chandrasana/Eight Crescent Moon

When the arms are in flexion the scapula is elevated and upwardly rotated.

2 – Extension - Seated arm warm up & Ashta Chandrasana/Eight Crescent Moon with clasped arms

When the arms are in extension the scapula is depressed and downwardly rotated.

3 – Abduction - Virabhadrasana II/Warrior II

When the arms are in abduction the scapula is upwardly rotated.

4 – Adduction - Garudasana/Eagle

When the arms are in adduction the scapula is in downward rotation.

5 – Internal rotation - Seated arm warm up & Parsvotanasana/Intense Side Stretch

When the arms are in internal (medial) rotation the scapula is in protraction.

6 – External rotation - Seated arm warm up & Gomukhasana/Cow Face

When the arms are in external (lateral) rotation the scapula is in retraction.

7 – Scapula protraction - Marjaryasana/Cat & Chaturanga Dandasana/Four Limb Staff

Scapula moves away from each other.

8 – Scapula retraction - Bitilasana/Cow & Urdhva Mukha Svanasana/Upward Facing Dog

Scapula moves towards each other.

Subscribe to my newsletter & get a FREE YOGA BENEFITS INFOGRAPHIC as a thank you!

To save the images for personal use click and hold down the image until the ‘save image’ option appears; on Mac hold down ‘control’ and click the image to get the option box; on PC right click on the image to get the option box. Scroll down in the ‘option box’ and click ‘save image’.

Ruth Delahunty Yogaru